The first dogs used for police work in the United States were introduced in New York City and Glen Ridge, New Jersey, during the first decade of the 20th century. Before this time, dogs were used occasionally for “crime control” in the South by plantation owners who sent the dogs after runaway slaves.

Table of contents

- New York Murder

- The Ghent Dog Program

- Preferred Dogs

- Wakefield in Ghent

- To New York by Ship

- Establishing a School in New York

- Training Commences

- Muzzles

- Program Grew

- The Staten Island “Pants Burglar”

- Other Success Stories

- Guarding Warehouses and Department Stores

- Detection Dogs

- Horror of Dogs in the South

- One Last Story

- Dogs Today

Share to Google Classroom:

New York Murder

In 1907, the brutal murder of 15-year-old Amelia Staffeldt in Elmhurst, New York, inspired the New York police administration to consider using dogs for police work. The man who murdered young Amanda was caught a few days later, and they learned that Henry Becker remained in Elmhurst for a day or so after the murder. If they had caught him then, they could have prevented his other crimes.

The police commissioner wanted to investigate whether a dog could have helped. He knew that a man on his force, Lt. George R. Wakefield, was also very interested in using dogs on the police force. Since the murderer remained in Elmhurst, the commissioner and Lt. Wakefield speculated that if they had a bloodhound, they could have caught Henry Becker sooner.

A kennel near Poughkeepsie, New York, specialized in raising and training bloodhounds. The commissioner sent Lt. Wakefield to investigate whether they should add a bloodhound to the force.

Wakefield returned from Poughkeepsie with depressing news. Based on what he learned about bloodhounds, he determined that the dogs would not be well suited to work in the city. The streets are layered with smells, and since criminals sometimes escaped by subway, it would be difficult for dogs to retain the scent. This would leave the bloodhound and policeman at a dead end.

The Ghent Dog Program

But the commissioner and Wakefield remained hopeful about using police dogs. A program in Ghent, Belgium, was receiving attention for the job they were doing training dogs to accompany constables for night patrol.

The commissioner funded Wakefield to go to Belgium to learn more.

The training program in Ghent started in 1902. The school created a four-month training program. The dogs were taught the tasks they would need: seek, attack, and then stop and hold. At that time, the dogs were not expected to bite their victims so they wore loose-fitting muzzles so they could still bark but not bite.

Since the dogs wore muzzles, they needed to learn another way to catch and bring down their victim. Most used a system that involved chasing down the person and wrapping their front paws around the fellow’s leg to bring him down. The dogs were then trained to stand on the person, barking to alert their dog handler.

Preferred Dogs

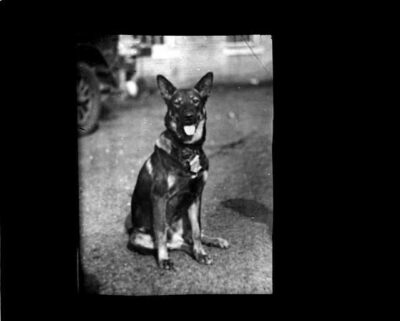

In Ghent, Belgian sheepdogs were the preferred dogs. They were known for their loyalty, courage, intelligence, and endurance. The breed at that time featured dogs that weighed about 50 pounds. They were barrel-chested and stood about knee-high to most men. They had short fur so upkeep was not an issue.

The Groenendael dog was a close second. These dogs matched the sheepdogs in temperament, but they had long silky black hair. This meant some grooming was necessary. (Poodles were not used as war dogs for the same reason. Their hair became matted when wet.)

Wakefield in Ghent

Lt. Wakefield spent several weeks in Ghent, working with some of the dogs and going through training himself. In the final analysis, he felt that these dogs could be helpful in New York City.

When Lt. Wakefield had the “okay” to bring dogs back to the U.S., he was disappointed to learn that there were no trained dogs available for purchase. The Paris police department was a big proponent of police dogs and had just purchased 400 of them.

Wakefield’s next step was locating dogs that could be trained. He finally made a deal for five six-month-old dogs. Four of the dogs were Belgian sheepdogs. One of them was a Groenendael.

He paid $10 for each pup, and another $10 for transatlantic travel for each dog. There was also an import tax of $2. This brought the grand total for each untrained dog to $22.00. (Trained dogs today cost between $12,000-$50,000. The dogs themselves are monitored carefully as both police departments and the military consider them valuable assets.)

To New York by Ship

George Wakefield used transatlantic travel via shipboard to work on training the dogs. They were still young. The dogs still needed to learn basic commands and have them reinforced.

Unfortunately, one of the dogs died before the end of the trip. There were no vaccines for distemper at that time, and many young dogs did not survive it.

Establishing a School in New York

Upon landing in New York, Wakefield and his charges were sent to a dilapidated mansion in Fort Washington Park in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan. Since they were short one dog, Wakefield replaced it with a young Airedale named Jim. The other dogs were Nogi, (the Groenendael), Max, Dona, and Lady.

Lt. Wakefield organized a 3-month training program to operate from Fort Washington Park. A patrolman known to be good with dogs moved into the mansion with his family to assist Wakefield. The dining room was set up with stalls where the dogs lived when they weren’t working or in supervised play.

The program, like the one in Ghent, featured positive reinforcement. Care and feeding of the animals was only done by men in uniform. That way the dogs learned that people in uniform were their friends and authority figures. People in civilian clothes were potentially suspect.

Training Commences

The initial plan for these dogs was for night patrolling. They were taught four commands: “Search!” “Attack!” “Heel,” and “Down.” Down was the command for the dog to back off and let the police officer take over.

When searching a house, the process was for the policeman to take the front of the house, sending the dog to search the yard, fields, and hedges.

An added benefit to the program was that police saw that the dogs were intimidating to the public. This alone helped reduce crime because people were nervous about what the dogs might do.

As training methods advanced, sound was one of the elements added. When the dogs were housed in kennels, audio could be piped in. By playing recorded sounds of thunderstorms, roaring car engines, and exploding bombs, it helped the dogs acclimate to what might happen on the street.

Muzzles

While today’s police dogs are often expected to attack with teeth, the first police dogs were muzzled. The muzzles were spacious enough that dogs could easily bark to sound an alarm. The muzzles also were equipped with snap catches. The dog handler could unmuzzle the dog quickly if more force (biting) was necessary.

Program Grew

By 1911, New York was using sixteen dogs for patrol in residential districts on Long Island. The dogs were assigned territories and could run on their own with their police handler nearby. From 11 pm to 7 am, the dogs brought down civilians (potential thieves) in the area. The dog was to stand on the person, barking until their handler arrived. (There may have been outcry from residents who were simply coming home late, but to my knowledge no reporter of the day wrote that story.)

By 1929, New York was using 23 dogs. There were many specific anecdotes where they proved their worth. One of the first was with the “Pants Burglar.”

The Staten Island “Pants Burglar”

In the 1920s, Staten Island was plagued by a robber who acquired the nickname, “the Pants Burglar.” The fellow climbed up porch trestles in his socks and snuck into upper floor windows. While the family slept, he moved quietly and quickly, leaving most possessions in place. He knew that if the family had cash, it was likely to be in the husband’s pant pockets. In the dark, he located the trousers, often draped over a chair or a bench. He then stole the items in the pockets. If he felt rushed, he sometimes climbed back out the window carrying the trousers with him.

Because the Pants Burglar struck so often, the police department finally selected four of their finest dogs to put on the case.

Within a few days, the dogs found their man.

Other Success Stories

One of the arguments against using dogs concerned the fact that more people were traveling by car. How could a dog help catch then?

That question was answered when policemen stopped two men in a car. The men got out as instructed, but within a few moments, one of the men turned to run. Fortunately, the policemen had a dog with them. Their dog immediately set off to chase the man and bring him down.

In another instance, a dog saved a child’s life. Bum was trained to work around the scene of fires. When a little girl bumped into a street vendor’s charcoal cooker, she fell against it, and her clothing caught fire. Bum was nearby and immediately approached and ripped off the burning fabric. She survived.

Guarding Warehouses and Department Stores

During the late 1940s and ‘50s, department stores began posting dogs for guard duty. Dobermans were popular for this work and were used in both stores and warehouses.

A security officer still needed to be on premises, but the dogs were trained to walk a beat alone. At Marshall Field, the store’s warehouse had special buttons along the route. The dogs were taught to press each button as they passed it. The security guard knew if the dog did not signal every 15 minutes or so, then the scene needed to be investigated.

Detection Dogs

Not all police dogs are used for apprehending the “bad guys.” Many are used for detection. Dog handlers now know that all breeds of dogs have extraordinary ability to smell their environment and make sense of it. As police departments worked with dogs, they found they could choose the breeds that are easiest to work with as they can all be trained to sniff out drugs and bomb-making materials.

In the 1970s, the U.S. experienced a rash of bombings around the country, so bomb-sniffing dogs were in high demand. The Washington (D.C.) Bomb Squad provided a demonstration for reporters, showing that the dogs could clear a corridor lined with closed lockers (like in a school or a train station) in 2 minutes.

For a time, bomb makers tried adding pepper to disguise the odor of the bomb materials. Officers quickly realized that a sneezing dog is a sure sign of something that needed to be investigated.

Horror of Dogs in the South

In the late 1950s and ‘60s, the image of police dogs suffered greatly in the South. Birmingham public safety commissioner Theophilus “Bull” Connor was in his position for more than two decades. He was a segregationist who was fervently against any demonstration that protested his belief in white supremacy.

When the Freedom Riders and civil rights marchers came through Birmingham, Bull Connor stopped at nothing to halt the protesters, setting a poor example for the South. Photographs from the era show unarmed people (many children as well as adults) being brought down by attack dogs. The photos and videos from these days are horrifying.

One Last Story

A more heartening story of a police dog took place in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1980. Rags was out on patrol with a policeman in a dark parking lot. Rags sensed danger from someone who was prowling in the area. He pushed the patrolman who accompanied him out of the way. When the gunman fired, Rags took the bullet himself.

Rags suffered a spinal injury, so a full recovery was not possible. But as he improved the veterinarian recommended him for a desk job where he could be in charge of milk bone procurement.

He became the department’s official mascot and was given a medal of honor.

Dogs Today

Today there are approximately 50,000 active police K-9s in the United States. In police work, dogs are being used for everything from drug and bomb detection to helping locate missing people and uncover forensic evidence at a crime scene. (Dogs are also trained for many other purposes, ranging from medical needs such as sensing diabetes to aiding the blind. Scientists have also found numerous ways to use dogs to preserve the environment.)

When a police dog is ready for retirement, most dogs become pets, often with their handler’s family. Those who have been wounded present additional challenges for their owners. How can the family pay for ongoing medical care? The National Police Dog Foundation does what it can to raise funds so that these dogs can be with a family they love and have the care they need.

Once again, Kate has dug deep to compile a fascinating story about dogs. In Chicago (and probably elsewhere), police dogs have the title “Canine Officer” in front of their names to acknowledge their training, skills and importance to the force. And this is the first time I’ve heard of Working Dogs for Conservation–what a worthy grassroots organization to support. Thanks, Kate!

Another wonderful story! Great info on the history of Police Dogs. It’s always a pleasure to see your latest articles in my email inbox! I recently found your youtube channel, as well. My husband and I enjoy these quick videos during dinner.

Linda, thank you!

Thank you! And yes, on my list of dogs to write about are some of the dogs being used for conservation…amazing stories!

Kate