Presidential candidates of today usually have non-stop schedules. Between fundraising parties and campaign appearances, they have a long list of people to see and things to do. Though Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris got a late start, she set a daunting plan for traveling the country so that people will have a better idea of who she is and what she believes.

Was it always like this? No, not at all. The practice of campaigning has changed greatly over 250 years.

Table of contents

Unseemly to Campaign

During the election era of George Washington and the founding fathers, any sort of travel was on horseback or by carriage, so it was difficult and slow. Fortunately, the custom was that candidates should not travel—that it was “unseemly” to ask for votes.

To promote a particular candidate, their friends took on letter-writing campaigns. They wrote to acquaintances near and far to explain the benefits of voting for their preferred candidate.

Election Day

The only way to vote at that time was to cast your ballot in person. Many Americans had farms, so they took care of their chores early, so they could come in to town to vote and visit with neighbors.

Voting took place on the village green. The women always set up buffet tables with copious amounts of food for everyone. A town meeting to resolve local issues generally preceded the general vote. Throughout the day, there was plenty of alcohol, generally paid for by the candidates. At some point the election was held.

The Country Grows

As the country grew, voting became more complex because there were state and national votes to process. Despite the fact that candidates could no longer meet each citizen before voting took place, campaigning from town to town was still considered in bad taste–vote begging, some called it. (Today’s candidates would probably be thrilled if we all looked down on them for traveling!)

Political Parties Become Important

As political parties grew, they took on campaign activities to make their candidates publicly known. The 1840s and 1850s were the beginning of these events. Like the voting on the village green, these events were fun for citizens who were generally isolated on their farms and worked long days.

Campaign rallies were held in large fields, and there might be several stump speakers addressing crowds in different parts of the field. (They were called stump speakers because they spoke from tree stumps.) There was always plenty of food and alcohol.

Parades sponsored by the political parties were also popular. Some stretched for miles with most people joining in rather than just watching.

Travel Begins

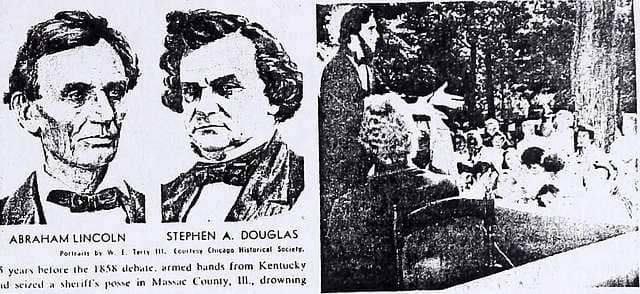

By 1860, throughout the country, there was great tension over slavery, and candidates began traveling.

Stephen Douglas was the first. He personally advocated that the slavery issue should be resolved locally—that it was a dying institution and there was no need for a federal solution. But when he won the Democratic nomination for president, the Democrats in the South refused to back Douglas. They split off to nominate John C. Calhoun, who defended both states’ rights and slavery.

Douglas was very concerned about the fate of the country and decided the only thing to do was make his case to the public—even if it meant traveling. Because campaign travel was not considered acceptable, Douglas decided that the best approach was to plan a visit to Clifton Springs, New York, to visit his mother. He was simply going to make a few stops on the way.

Republicans Aghast

He announced his planned trip, and the Republicans were on to him. They issued a handbill making fun of Douglas. Douglas was short in stature, so they headlined the handbill:

“A Boy Lost!

“A Boy Lost! Left Washington, D.C. sometime in July to go home to his mother. He has not yet reached his mother, who is very anxious about him. Douglas has been seen in Philadelphia, New York City, Hartford, and at a clambake in Rhode Island. …He is about five feet nothing in height and about the same in diameter the other way. He has a red face, short legs, and a large belly. Answers to the name of Little Giant, talks a great deal, very loud, always about himself…”

Travel Becomes Customary

When the Civil War ended and elections became somewhat more normal, candidates began to travel to campaign. Foremost among them was Democrat William Jennings Bryan. He was a powerful speaker and people loved coming out to hear what he had to say.

In 1896, the Republicans nominated Ohio governor William McKinley. His campaign manager, Marcus Hanna, knew that going head-to-head against the charismatic Bryan on the campaign trail would be a lost cause. Hanna implemented something new.

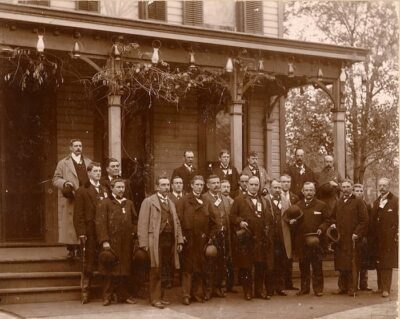

The Front Porch Campaign

Marcus Hanna created what he called a “front porch” campaign. McKinley lived in Canton, Ohio, at the time. Hanna arranged for special trains paid for by the Republican Party. Then he offered free rides for all who wished to come in to meet the candidate. The trains ran from July to November, and it was quite a festive occasion.

As the trains pulled into the Canton station, a mounted brigade and a band met the passengers. The newcomers were then escorted to McKinley’s home. When the music slowed, McKinley stepped out onto the front porch to give an address, thanking the people for coming and asking for their votes. On one day alone it was estimated that McKinley spoke to some 30,000 people.

Visitors brought gifts of flowers, food, and flags, which was lovely. But they often wanted souvenirs from their visits. Some plucked flowers or blades of grass. Others broke off parts of the wooden fence—even bits of the front porch–and to take home.

By the end of the campaign, the lawn and fence were gone and the porch was in a state of disrepair…. But of course, it worked… McKinley won.

Local Candidates Worked Hard, Too

While the preceding stories are of campaigns for national office, we can’t forget how hard local candidates work. In my research, I read of a candidate for sheriff carrying along a box of cigars and a quart of liquor.

Another candidate kept a diary of what it took to get elected. In one case, he traveled 30 miles on horseback to visit a ranch where two voters lived. Because the rancher couldn’t take time to stop and talk to him, the candidate and his traveling companion pitched in. They helped vaccinate calves (and “ruined a $5 pair of breeches dipping sheep” in the process) while presenting the issues to the rancher.

At another ranch, the owner was very proud of his horse. The candidate recognized how much this horse meant to him, so he left and returned with a photographer. A handsome photo of the ranch owner and his mare resulted. All three of the family members voted for that candidate for sheriff.

Every Vote Counts

Every vote in West Texas counted! Just as the votes do today.

Please vote. Take your neighbors and friends along, too.

Very well written and interesting article, Miss Kelly. Great information. I highly enjoyed it, as always. Keep up the great work!

Thank you!