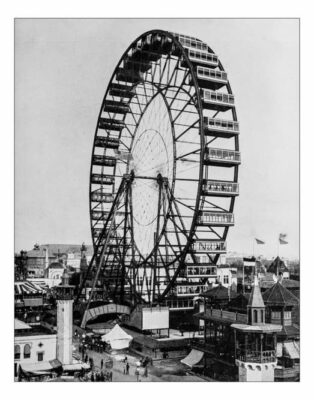

The first Ferris Wheel—known as the Big Wheel—was constructed for the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. It dazzled and then it was gone.

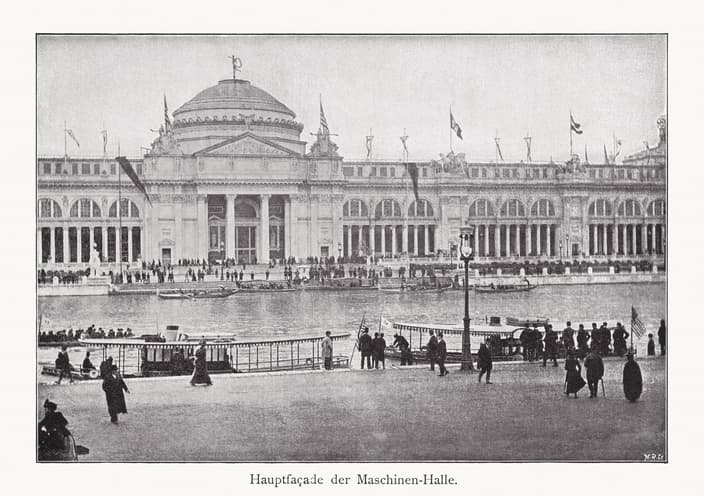

This world’s fair was to celebrate the 400-year anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the New World. (Columbus was viewed differently at that time.) The fairgrounds were slated for Jackson Park, a little-used part of Chicago on the south shore of Lake Michigan. Organizers felt it would revive and bring business to the area.

The architect hired to be the on-site director of the Exposition was Chicago architect Daniel Burnham. Other planning luminaries were to join him, including landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead, and architects Charles McKim and Richard M. Hunt.

As the group made plans, all eyes were on the Paris Exposition of 1889. The creation of the magnificent wrought-iron Eiffel Tower put Paris on the map for tourists and continues to be admired. (It was a featured part of the 2024 Summer Olympics.) All of the men wanted something that would out-shine the Eiffel Tower.

What could compete?

Table of contents

Share to Google Classroom:

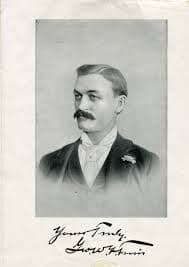

In 1891 at a luncheon of engineers meeting in Chicago, Daniel Burnham offered a challenge: He wanted the men (and it was a room filled with men) to submit awe-inspiring ideas that could be featured at the Chicago Exposition. He wanted something “original, daring, and unique”—something stunning and memorable that would bring people to Chicago. George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., a Pittsburgh civil engineer and bridge builder, attended the luncheon where Burnham issued the challenge. Ferris had an idea that he felt could work. Over the course of the following winter, Ferris submitted his plan to the committee for a Big Wheel—a giant structure almost 300 feet tall. It would rotate vertically with 36 cabins (gondolas) carrying passengers. He envisioned it as part amusement park ride and part observation tower. Riders would be able to see spectacular views of the surrounding city and lake. The height was only one-third of the Eiffel Tower but the ride would provide the thrill of a lifetime. Ferris’s idea garnered little support among committee members. As Burnham worked on the gracious urban plan he foresaw for the White City, the idea of an oversized steel structure—even one that moved– did not appeal to him. Initially, Burnham and his committee rejected all the suggestions they received, including that of the Big Wheel. The planners actually made fun of Ferris, referring to him as “the man with wheels in his brain.” At some point, the Wheel was described as a giant black spider web. That wasn’t what Burnham had in mind. George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. was born in 1859 in Galesburg, Illinois. The town was founded by George Washington Gale, a Presbyterian minister. Both Ferris and his father were named for the town founder. Despite family roots in Illinois, Ferris’s father decided to move west. He had knowledge of landscaping and horticulture. In 1864, when the family settled in Carson City, Nevada, he was hired to help plan the town, bringing in many plants from the East. George Ferris Jr.’s interests lay elsewhere. He wanted to learn how things worked. For high school, he attended a military academy in Oakland, California, and then he enrolled at Rensselaer Polytechnical Institute in Troy, New York, He graduated from RPI in 1881 with a degree in civil engineering. His passion was for bridge building. His first job was with a railroad company where he worked building train bridges. A few years later, he founded his own company, G.W.G Ferris & Company, based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His specialty became testing and inspecting metals for railroad and bridge builders. He consulted for companies nationwide. There was nothing particularly new about a vertical rotating wheel. Water wheels date to Mesopotamia and were an early source of power was employed until water power could be replaced by electrical power. What was different was the size and the use of the Wheel. Ferris was not first in seeing it as an entertainment mechanism. At about the time that Ferris was working on his plans, a carpenter named William Somers installed three 50-foot wooden wheels (described as vertical merry-go-rounds) at amusement parks around New York and New Jersey (Asbury Park and Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Coney Island, New York.) In 1893, Somers received a patent for what he called the “Roundabout.” (US Patent 489238A) Somers’s plan was for a vertical carousel. The patent does not specify the size of the cabins (the seats for riders), but in an old photograph from the 1890s, it would appear that Somers’s roundabouts provided bench seating for 2-3 people—much like what Ferris wheels feature today. Ferris was said to have ridden on one of Somers’s wooden roundabouts, but because he must have already been working on his design, the experience may have simply confirmed what he was thinking. Ferris heard Burnham’s call for something “big,” and his plans were for a wheel that would extend 264 feet in the air with cabins that could hold sixty riders in each unit. When fully filled with passengers, 2160 riders could be aboard the giant ride. The plans specified the construction of two 140-foot steel towers to support an axle with two parallel wheels. These towers were spaced 30 feet apart and connected by metal bracing that held the dual wheels together. The axle needed would be the largest ever forged. It was to be made in Pittsburgh and was 45 feet long and 32 inches in diameter. It weighed almost 90,000 pounds. The wheels would be powered by two 750-horsepower engines. As they turned on the axle, they traveled on what appeared to be a large bicycle chain. The cabins for passengers would be made of wood but were glass-enclosed. They hung from iron clamps on rods between the two giant wheels. Double doors would provide entry into the space, and a conductor would ride in each cabin. The conductor served the dual purpose of being there to answer questions but also to keep people calm if someone became anxious. The months were passing, and there was still no decision from Burnham. Ferris spent $25,000 of his own money to work out plans and create models of the Wheel. He also received some initial investment from others. As he went forward, he could assure Burnham that the Exposition would not have to bear the full cost. In late December 1892, Daniel Burnham still had not selected the proposal for the “one big thing” for the Exposition. He knew he needed to take action. As the fairgrounds took form, the buildings were all being designed in white in a Classical Revival style of architecture. The planners were referring to the area as the White City. Burnham realized he needed to make a decision, and Ferris was the best offer he’d had. However, Daniel Burnham did not want the Big Wheel in the heart of his stunningly beautiful fairgrounds. There was going to be a Midway on Central Avenue. Burnham decided the best thing to do was give Ferris the okay but put the Wheel on the Midway. But how was this going to be accomplished? Bridges took years to build. How was a moving wheel that needed to be safe for passengers going to be completed in fewer than six months? Ferris was a gifted engineer who knew his vision was sound. Because he worked from detailed plans, he was able to spring into action quickly. At that time, Ferris was head of Pittsburgh Iron Manufacturing Company and was also often called upon for bridge inspections. This gave him knowledge and connections to steel manufacturers. These connections were key to getting the Big Wheel underway. When the go-ahead came, Ferris knew he needed four thousand tons of steel—more than any one plant could assemble quickly. He took his detailed plans, and he farmed out assignments to nine large steel plants. As the sections were built, they were shipped to Chicago for assembly. The foundation was the next challenge. Ferris hired L.V. Rice to work as construction supervisor for the foundation, which would be expected to hold 1300 tons (or two million pounds). There would be eight struts (two towers) supporting the 45-foot axle around which the two giant connected wheels would circle. Rice and Ferris knew the foundation needed to be deep to hold that tonnage. If the Big Wheel was to be ready by a spring opening, the foundation would need to be dug starting in January despite the cold Chicago winter (negative 10 degrees on many days). Initially, Rice dynamited the ground to start the foundation pit. After three feet of dirt was removed, Rice began piping in steam heat so the men could dig. The pit was planned for 35 feet below the surface to be sure there was sound footing. The steam heat kept the cement from freezing prematurely as they laid the foundation from below. As the pieces arrived from the various steel mills, workers assembled the parts. At night, 1400 (one source said 2500) incandescent lights shone brightly over the fairgrounds, the city, the lake and the prairie. Ultimately the Big Wheel cost $380,000 to build. At 264 feet (80.4 meters) high, it was the largest wheel in the world– five times the size of the largest wooden “pleasure wheels” of the day. The Big Wheel was not quite ready when the Columbian Exposition first opened but guests didn’t have to wait much longer. The Big Wheel was open for operation by June 21, 1893. The first riders were invited guests, but soon regular passengers began paying 50 cents per ticket. The Wheel was a huge hit. It took 20 minutes to complete two revolutions. There were two platforms where passengers could board or get off the ride. The first revolution was for loading and unloading the cabins. The second revolution was made without stopping so people could travel full circle with no interruption. Nearly 1.5 million Ferris Wheel tickets were sold throughout the fair, slightly more than the population of Chicago at the time. Amazingly, it ran without a hiccup—totally trouble-free— all the way through to the closing of the Exposition on October 30, 1893. It was a perfect experiment that was copied widely at amusement parks throughout the country. In a newspaper article of the day (The Chicago Inter Ocean, August 2, 1893), Ferris told a reporter that after 300,000 riders had experienced the Big Wheel, one customer approached him for a refund. When Ferris asked why the fellow wanted his money back, the man said he felt cheated because there was no sensation of movement. Ferris was delighted. In all his planning, his goal was to provide a seamless ride. The fellow was cheerfully given a refund on the ticket. When the Exposition closed, George Ferris and his investors were unhappy with their financial take. Ferris entered into the project having already arranged for much of the funding. The final agreement was that Ferris would retain $300,000 from the sale of the tickets, after which the gross receipts were to be split between Ferris and the Exposition. When the Exposition ended, Ferris began litigation. During that time, the company was looking for where else the Wheel could operate. Finally, a new site in Chicago was found. It took 86 days to dismantle it and more time to set it up. The next location was on Clark Street near Lincoln Park where hotels and retail were to be built. But nothing ever happened. The Wheel sales suffered. When the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis was in the planning stages for its 1904 opening, the Big Wheel was a logical addition to the St. Louis fairgrounds. It was a success there but when the Exposition closed, there was no one left to champion the magnificent Big Wheel. It was blown up with dynamite and then chopped up and sold for scrap. What had happened to Ferris? He met an unfortunate end. In early 1896 when he was only 37 years old, he became ill from typhoid fever and was admitted to Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh. He died November 22, 1896. So was the Big Wheel a success or a failure when compared to the Eiffel Tower? At first one would think the Eiffel Tower was the most successful icon. It still stands and attracts millions of tourists each year and played a prominent role in the 2024 Summer Olympics. But its success lies in its singularity. There was no need for others to replicate the Eiffel Tower. The one in Paris was good enough. But the Big Wheel? Even at only one-third of the height of the Eiffel Tower, it was a marvel. Today we have Ferris wheels (as they came to be known) at every amusement park around the world. In addition, there are gigantic observation wheels like the London Eye, the Singapore Flyer, and the High Roller in Las Vegas. If success is measured in imitation, then one has to say that the Big Wheel—the Ferris Wheel—in Chicago is the true victor. To read about another creation/invention of this era, read about Who Thought of the Statue of Liberty? *** Special thanks to historian Douglas Westfall for encouraging me to dig out my file on the Ferris Wheel. Doug’s company, The Paragon Agency, specializes in publishing first-person narratives that bring the past to life. Check his website for hundreds of offerings.A Challenge

George Ferris Had a Plan

Who Was George Ferris?

What About the Big Wheel?

More About Ferris’s Plans

Time Ticked By

Moving Forward

Building the Foundation

The Opening

Refund Requested

The Exposition Closing

What Else to do with the Wheel?

On to St. Louis

Success or Failure?